Leave John Wayne Alone

December 6, 2010 § Leave a comment

More than 30 years after his death, John Wayne still can’t get a little respect. The latest sideways attack, in the pages of The New York Times, seems as unnecessary as it is unfounded. It came in the form of a formless and unfocused article by Michael Cieply (published Dec. 3), headlined “Coen Brothers Saddle Up a Revenge Story (or Two). Maybe Cieply needed to denigrate Wayne in order to fawn over Joel and Ethan. Who knows?

I wonder, for the record, how all of this makes Jeff Bridges feel. Bridges is inhabiting the role of Rooster Cogburn in the Coen’s new film. Let’s see, Bridges won his “only” Oscar (so far) last year for a movie called … hmmm. What was the name of that movie again? Thank God Bridges wasn’t viewed as a sentimental favorite at all last year.

I wonder, for the record, how all of this makes Jeff Bridges feel. Bridges is inhabiting the role of Rooster Cogburn in the Coen’s new film. Let’s see, Bridges won his “only” Oscar (so far) last year for a movie called … hmmm. What was the name of that movie again? Thank God Bridges wasn’t viewed as a sentimental favorite at all last year.The Rhythm Man: Drummer Colin Bailey Has Played Jazz With (Fill In Just About Anybody Famous Here)

December 1, 2010 § Leave a comment

But we have to go back to where Bailey started learning his art: Swindon, in the UK. After all, he knew he was going to be a drummer from the start.

Bailey had his first lesson on the drums when he was seven. “It was with a guy that worked in a local vaudeville show. My dad said this guy had a ‘nice, crisp roll’, and I went to this guy and he had the worst left-hand grip,” said Bailey. “He had a terrible grip, but he taught me about arrangements so he was very good for me at the time. Then when I was 10, there was a man named Peter Coleman who was with a band called Johnny Styles, which was one of the better semi-pro bands in England. They won contests and things like that. Peter was the drummer for them and he used to come over to my house and he taught me how to read drum parts.”

Bailey had his first lesson on the drums when he was seven. “It was with a guy that worked in a local vaudeville show. My dad said this guy had a ‘nice, crisp roll’, and I went to this guy and he had the worst left-hand grip,” said Bailey. “He had a terrible grip, but he taught me about arrangements so he was very good for me at the time. Then when I was 10, there was a man named Peter Coleman who was with a band called Johnny Styles, which was one of the better semi-pro bands in England. They won contests and things like that. Peter was the drummer for them and he used to come over to my house and he taught me how to read drum parts.” |

| Winifred Atwell |

About the time Bailey turned 18 he received an invitation to audition for a pianist named Winifred Atwell – a name that may not be familiar today, but who was a rising star at the time. Bailey joined her band and she would go on to become quite famous. There’s a lovely clip of Atwell being hosted on the Australian version of “This Is Your Life”, during which the host tells Bailey to sit on the couch with Atwell because “you’re her family.”

|

| Joe Morello |

A turning point in Bailey’s evolution as a drummer came in 1956 when he heard drummer Joe Morello play on a Dave Brubeck record. There is always someone, in the career of any artist, who plays the important role of mentor – the person who makes the artist want to be better all the time. For Colin Bailey, that person is Joe Morello. Morello is known for his unique time signatures like the ones that can be heard on such legendary recordings as “Take Five.”

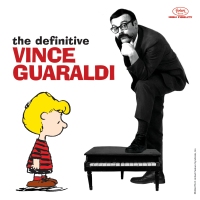

Guaraldi was not a prolific writer, but he made his mark. “Vince wrote great – what I call ‘catchy tunes’ that people could get into. They weren’t complicated. “Cast Your Fate To The Wind” and all these things, we were playing every night,” said Bailey. Guaraldi had a contract with Fantasy Records (which was based out of San Francisco) and we went into the studio at midnight and did the whole thing in four hours. I absolutely love that record.”

|

| Ben Webster |

“It was an honor – what an honor – to play with Ben Webster. Ben was an original. No one sounded like Ben. He had come to the Jazz Workshop with Jimmy Witherspoon and we played a three week gig, six nights a week, and Sunday afternoons,” said Bailey. “I got to hang out with him a little bit. He was playful. It would be like 3 o’clock in the morning and he would eat this big bowl of chili. He had an cast iron stomach. He was a beautiful person.”

But Bailey played on the Francis Albert Sinatra/Antonio Carlos Jobim album that was released in 1967. It may be the last great album Sinatra ever made – not that he didn’t record some beautiful singles, but the great Sinatra concept albums were all behind him by the late 1960s. While Sinatra’s later records as a whole tended to try too hard to be current, the beauty and clarity of the Jobim record is undeniable, and Sinatra may not have ever sounded better.

“I was influenced by all kinds of people. I mean, for instance, I was influenced by a drummer named Joe Daniels in England when I was about seven years old. He had a Dixieland band. There was Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Shelley Manne. Shelley was one of the great drummers. He was wonderful to me. He gave me so much work. I used to sub for him at the club (Shelley’s Manne Hole) with his group. Max Roach – he just blew me away, that was in 1950, 1951,” said Bailey.

“I was influenced by all kinds of people. I mean, for instance, I was influenced by a drummer named Joe Daniels in England when I was about seven years old. He had a Dixieland band. There was Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Shelley Manne. Shelley was one of the great drummers. He was wonderful to me. He gave me so much work. I used to sub for him at the club (Shelley’s Manne Hole) with his group. Max Roach – he just blew me away, that was in 1950, 1951,” said Bailey. Todd Hunter’s "Summer Blink": A Review

November 29, 2010 § Leave a comment

By Lars Trodson

|

| Tana Sirois |

The factors that make truly independent cinema so thrilling are wholly on display in Todd Hunter’s recently released feature film, “Summer Blink.”

“Summer Blink” is thrilling because you’re able to watch new talent emerge, and to see how smart filmmakers ingeniously overcome the obstacles of a budget that doesn’t allow for extravagant locations or huge extra-filled scenes. Thrilling also because its a high-wire act during which the audience can sometimes see the artists wobble — only to have them recover and walk triumphantly over to the other side.

Hunter, who wrote and directed “Summer Blink”, has created a mature work. He’s a theater director making his first venture into film, and he has assembled a great cast that he handles with astonishing dexterity. I say mature because Hunter not only shows a remarkable affinity for the unique demands of film, but also because his film treats issues such as sex and wanderlust without the fawning romanticism you see in most American movies.

There are many moments in this film, big and small and sometimes seemingly inconsequential, that are exactly right. When they accumulate you feel, as you should in any film, that you’re watching something private. Rarely are films (of any kind) so well observed.

|

| Todd Hunter directing “Summer Blink” at Cafe On The Corner in Dover, NH. |

“Summer Blink” tells the story of Mina (played by Tana Sirois) and her moment of discontent. All her friends are graduating from high school – the exact city is never named – and everyone is headed off to college and making plans for the future. Mina, however, is directionless and penniless and she’s sour. She’s taking her frustrations out on her boyfriend Jake (Jeff Bernhardt), who is anything, thank goodness, but a cliche. He seems like a good person and a great boyfriend, and the dynamics between Jake and Mina are wonderfully played out.

Jake and Mina break off, and Mina finds herself drifting towards Alison (played by Ashley Love). Their budding relationship forms the heart of the film, and Hunter does a great job in filling in the arc of their story. Sirois and Love are superb together; they are beautifully unmannered performers.

Sirois is in every scene in the film — the camera almost never strays from her, in fact – and she may be the real deal. She has old-school Hollywood beauty, and, in the truest tradition of screen acting, you can’t see her wheels turning. She doesn’t wait in a scene to speak her line; she’s listening to what others have to say, and she reacts to that. The way she reads a line reminds me of Myrna Loy, who could give sound and color to a grocery list. This is a fully realized performance by an actor one suspects will go very far. Let’s hope Hollywood gives her parts as well-written as this.

Ashley Love is also great. She never seems forced and there is an emotional honesty and intensity between her and Sirois. She’s got less to work with than Sirois — Alison is enigmatic; her motivations are more obscure — and that’s very tough to pull off, but she does an exquisite job.

|

| Sirois and Ashley Love |

Some quibbles: There are a few attenuated scenes that can be shortened. A couple of scenes establishing the mood of the lead character, Mina, could easily be shaved without disrupting the film’s rhythm or costing the audience any much-needed information about the characters. There are three very long scenes (the first lasts more than 10 minutes) between lead actors Sirois and Ashley Love that tend to go on even after the audience has learned enough about what is happening to the characters.

There is one sound issue that Hunter and his crew have tried to gamely overcome but needs to be addressed because it blunts our reaction to what should be the emotional climax of the film. It’s an important moment late in the film, but two-thirds of the way into this terrific scene the dialogue is suddenly drowned out by music, even though Sirois and Love keep talking. If this was an aesthetic choice, it was a mistake, but I doubt it was. The sound may simply not have been recorded well enough to use (the perils of independent film). I feel Hunter left it in because it showcases a big moment for leading actress Sirois, and he tries to salvage it, but perhaps there is a way to get the two actors to loop the dialogue and complete the scene as shot.

But these are only distractions because the rest of the film is so good.

All the actors all display a pleasing naturalness — even the minor characters that drift in and out. There are some catty girls at a party and at graduation that are nice flourishes that Hunter stages wonderfully. Dylan Schwartz-Wallach, as Mina’s brother Evan, has a brotherly goofiness that’s just exactly right. The lovely score is by Seiken Nakama.

You need to seek out “Summer Blink.” You’ll form your own ideas about what works and what doesn’t. Todd Hunter has made a fully realized, beautifully crafted feature film — and if you think this is easy to do ask anyone who has ever tried it. It’s independent film in all of its independent glory, and a real accomplishment for Hunter, Sirois and team. We need more stuff like this.

“Summer Blink” is a Rolling Die Production. Produced by Jasmin Hunter. Cinematography by Kristian Bernier. Music by Seiken Nakama. Edited by Paul Buhl. 124 minutes. Cast: Mina – Tana Sirois; Alison – Ashley Love; Jake – Jeff Bernhardt; Evan – Dylan Schwartz-Wallach; Chris – Matthew Cost; Elise – Erin Adams; Wendy – Joi Smith.

Haven’t Seen ‘Bighorn’? Check It Out Right Here

November 29, 2010 § Leave a comment

http://player.vimeo.com/video/16321576?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&color=ff9933

Our friend Freddie Catalfo’s short film “Bighorn” continues to make the rounds at festivals and generate buzz. Wondering what it’s all about? See it right here. Catalfo describes “Bighorn” as “a 15-minute, supernatural historical fantasy based on a true fact: that General Custer’s bandmaster, Felix Vinatieri — an Italian immigrant and the great-great-grandfather of Super Bowl-winning kicker Adam Vinatieri — was ordered to stay behind at the 7th Cavalry’s Powder River camp and missed the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The story takes place in 2002 and 1876. BIGHORN is the latest from award-winning filmmakers Alfred Thomas Catalfo (writer/director of the internet hit “The Norman Rockwell Code” and winner of 21 major screenwriting competitions) and Glenn Gardner (producer of Cannes Film Festival Palm d’Or winner “Sniffer”). The renowned Steve Alexander, recognized by the U.S. Congress as the world’s foremost Custer living historian, portrays Custer. Native American and adopted Lakota Bill Watkinson portrays the Lakota Medicine Man. The NFL graciously granted the filmmakers permission to use footage from the 2002 Super Bowl.”

Clint Eastwood, Jack Nicholson and James Franco Should Team Up To Make Jack Kerouac’s “On The Road”

November 22, 2010 § Leave a comment

“I hope you get where your going and be happy when you do.”

It sounds like an Irish blessing, something that has come down to us over the years, something that is said when people get married, have a drink, consecrate a death, or begin a journey. “I hope you get where your going and be happy when you do.” How much more simple and beautiful can you get?

But it isn’t an ancient blessing. It’s a throwaway line in Jack Kerouac’s “On The Road” — appearing on page 134 of the scroll version, and it’s said by an old hobo called Mississippi Gene that’s hitching a ride on the back of a truck out in the midwest. (The spelling used in the phrase is Kerouac’s.) It’s good, practical advice, something that sounds right coming out of the American mid-west at night, and I suppose this is what made me think of Clint Eastwood, and made me think that if there was anyone on the planet that could turn “On The Road” into an honest movie it would be him. Eastwood may be the last living, working American filmmaker who was around at the time the book takes place. He must have heard that language spoken in the book as it was actually spoken and travelled the open roads the story takes place on. “On The Road” was written between 1947 and 1949. This is a story of Wild West Week in Montana and old Indians hanging out at bus stations at night, and of off-road diners where you can buy beer at midnight.

Eastwood may be the last living, working American filmmaker who was around at the time the book takes place. He must have heard that language spoken in the book as it was actually spoken and travelled the open roads the story takes place on. “On The Road” was written between 1947 and 1949. This is a story of Wild West Week in Montana and old Indians hanging out at bus stations at night, and of off-road diners where you can buy beer at midnight.

Eastwood can remember that. He was born in San Francisco in 1930 and he would have breathed the same air and heard the same sounds Kerouac describes, like those parts when he’s stuck in Marin County and driving into San Francisco at night trying to pick up girls. Eastwood has that California cool in his bones. He’d be the perfect director for an “On The Road” film.

|

| Neal Cassady |

The heartbeat of the story is not just Kerouac, of course, who seems sadder and more disaffected in the scroll version than I remember in the heavily revised Viking version. There is also the famous madman Neal Cassady, who had a patois and joy of life that others around him (Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, etc.) found not only infectious but inspiring. Ginsberg wrote Cassady into “Howl” and of course Kerouac begins “On The Road” like this: “I first met Neal not long after my father died…I had just gotten over a serious illness that I won’t bother to talk about except that it really had something to do with my father’s death and my awful feeling that everything was dead.”

Neal Cassady would reawaken Kerouac’s zeal for life, and you get a feel for Cassady when Kerouac writes down the way he speaks: “‘Now darling here we are in N(ew) y(ork) and although I haven’t quite told you everything that I was thinking about when we crossed the Missouri and especially at the point when we passed the Bonneville reformatory which reminded me of my jail problem it is absolutely necessary now to postpone all those leftover things concerning our personal lovethings and begin thinking of specific lifework plans…’” This is how Kerouac recorded Neal Cassady.

And this made me think of Jack Nicholson. Nicholson (born 1937) undoubtedly knew the beat scene of the late 50s and he certainly was familiar with Ken Kesey, of course, because he had played Randall Patrick MacMurphy and Cassady had been an integral part of Kesey’s Merry Prankster’s, having driven the bus. But that isn’t why I thought of Nicholson.

When you hear or read an interview with Nicholson he has that kind of speech that you hear Neal speak above: Nicholson has a very unique, very specific way of speaking — something that rarely if ever comes through in his acting. It’s Nicholson jazz geometry. It’s concrete and oblique at the same time; and beautifully filligreed. And you never misunderstand what he’s saying. Nicholson has a fascinating personal language all his own. But since he’s also a writer, he would be the perfect writer to turn “On The Road” into a script.

Nicholson would get the hipster angle, and he would empathize (and probably sympathize) with the driving heartfelt artistry that is inside these characters, and their desire not to do what they are supposed to do but what they want to do. “This is the story of America,” Kerouac writes at one point. “Everybody’s doing what they think they’re supposed to do.” Nicholson understands the burning need to not do what you’re supposed to do, but to do what feels right, and to have that turn out right.

“I have finally taught Neal that he can do anything he wants, become mayor of Denver, marry a millionairess or become the greatest poet since Rimbaud,” Allen Ginsberg says at one point about Neal Cassady. “But he keeps rushing out to the midget auto races.”

This conflict — the outsider trying to play the insider’s game — is one that Nicholson has spent a lifetime delineating on film.

I was thinking then, as I read again through this beautiful book — one that has eluded filmmakers for more than 50 years — that Eastwood and Nicholson may be a great combination to give us this story on film.

We are also now blessed with an actor, James Franco, who would be perfect as Neal. Franco has that American handsomeness, and the keenness of mind and talent to play Neal Cassady.

This is my version of having a fantasy football league but only for movies. Eastwood at the helm, Nicholson as screenwriter (and playing Mississippi Gene so he can deliver that line), and James Franco as Neal Cassady.

One more thing: “On The Road”, unlike “The Great Gatsby”, still has relevance beyond the beauty of its language. The book still speaks to people on a visceral level. I realized this the other day when I went into Baldface Books, a used bookstore in Dover, NH, to get the standard paperback edition of “On The Road.”

“I don’t think I have any,” said the owner who, in fact, didn’t. “Anytime I get some copies, the kids come in and take them right off the shelves.”

The Great Gatsby: Is It Filmable?

November 19, 2010 § Leave a comment

Turning “The Great Gatsby” into a movie comes down to a central question: how well can you dramatize a single line of prose?

That single line is: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Gatsby is a great novel without much a plot. It’s a long lament. It’s a memory drifting away in the hot summer sun. But that line is a real thumper — it knocks everybody out when they first come across it — and it may be the one line everybody remembers aside of the very last beautiful line of the book.

In the 1974 film version, Sam Waterston plays Nick Carraway, and he delivers it in that halting, sideways style of his that dissolves all the power from it. And if you don’t get that line of the book right you don’t have the movie. Jack Clayton directed that version, and it starred Robert Redford as Jake Gatsby. We know it it all turned out.

“Gatsby” is uniquely American. The only culture in it is the culture of money. And that American-ness – that Jazz Age vernacular – is awfully difficult to synthesize. Harder still now that there isn’t anybody left that actually spoke it and lived it.

Baz Lurhmann has chosen an English actress, Carey Mulligan, to play Daisy Buchanan. Who could really play that role anyway — maybe Joan Crawford in the 1920s, when she was sexy and free? Before she became a bit mummified?

I have no doubts about Mulligan as an actress, I guess, but I’ve only seen her in one film. She seems extremely refined. Her beauty is refined. Daisy is beautiful but is it that kind of refined beauty? I don’t think so. Daisy is rich but she’s vulgar.

Leonardo DiCaprio is a fine, fine actor — but he doesn’t have a lot of mystery about him, and what is Gatsby if not mysterious? Who is he — what is he? When DiCaprio strays too far outside his acting range his face gets all crimpy and confused, and I don’t see Gatsby ever breaking a sweat.

Well. This new version may be dazzling. But the thing about “Gatsby” is that it was never about the story – it was about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s voice, and if that isn’t front and center of the film – and how can it be? – then what have you got?

Fitzgerald was a guy who caught the vibe of his age, but nothing from the 1920s, almost nothing at all, has lived into the 21st century, including its books, its magazines, its music and its movies. It’s a shockingly irrelevant time, from this vantage point.

I suspect, then, that the urge to make this story again as a film is based more on its myths than its merits. We have these bad film versions (including a Hollywood version from 1946, and a silent adaptation that seems to be lost), and maybe there is some kind of ego-driven desire to undo that, as though old Gatsby hasn’t gotten his due. Maybe DiCaprio feels that Gatsby is also a great role that hasn’t been done well, either. But that doesn’t hold up. Gatsby doesn’t leave his house. He broods. He’s a void. What do you do with that? You have to shift the power center of the book away from Nick to Gatsby to make it a starring role, and I doubt that will work.

For me, when I want to get a feel for the 1920s, I take out my old New Yorker cartoon anthology and look at the drawings made during that decade. They’re decadent, drunken vampires that saunter through those pages. Everybody’s drenched in jewels and regret. That’s what Gatsby feels like to me.

The 1920s were so wasteful and exhausting it didn’t even have enough stamina to finish on time. On Oct. 24, 1929 it all came to a screeching halt, burnt out to the core. Good luck with that.

Roundtable Pictures at NHFF

October 30, 2010 § Leave a comment

|

| Photo by Ralph Morang |

Roundtable Pictures’ short film “Tuesday Morning” was well received at the New Hampshire Film Festival. In the photo above, Lars Trodson, far right, of Roundtable Pictures answers a question about the film during a question and answer session at the Music Hall in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Should’ve Put More Cayenne Pepper Into The Sugar Bowl: Leon Russell and Elton John Make A Record

October 24, 2010 § Leave a comment

By Lars Trodson

If the background story of how a record got made counted toward its musical quality, then “The Union” would be a masterpiece. As it stands, it’s a moving reintroduction to one of America’s great lost singer-songwriters, and one that, with hope, will spur Leon Russell to go and make some more of his personal and idiosyncratic works all on his own.

You have to admire the passion that Elton John put into the project. After apparently hearing a song of Russell’s while on safari more than a year ago, John got in touch with Leon Russell himself, and with his producer, T. Bone Burnett, and in less than a year a veritable army of singers, musicians and Annie Leibovitz’s staff converged in L.A. to produce “The Union.”

It’s a meticulously made record, to be sure. Elton sounds as robust as ever, just as Russell’s reedy voice is cracked and unsteady. That doesn’t bother me. I like the late recordings of Frank Sinatra as much as any he ever made, those mediocre duets with a voice made haunting by too much heartbreak and booze and too many cigarettes. Russell’s voice on “When Love Is Dying” is as unvarnished as anything you’ll hear in a modern recording — it has a little Willie Nelson twang to it, in fact — but that makes it beautifully human in an era or airbrushed voices and digitized high notes.

But “When Love Is Dying”, as with all the songs on the record, is overproduced. It’s got a big group of background singers, and what should have been a delicate little tune comes totteringly close to a kind of Broadway showstopper. Russell tries to bring it back to earth, but he gets drowned out. (The background singing arrangement on this song was done by none other than Brian Wilson.) I know that Elton wanted to get Leon back onto a big canvas, but he and Burnett should have listened to what Rick Rubin did with Johnny Cash on his last recordings. Jesus, those are beautiful, and it could have been like that here.

The song that comes closest to this (but is still overbaked) is “Gone To Shiloh”, with verses sung by Leon, Elton and a very welcome Neil Young. Wait for the unplugged version of this to come out.

The other thing that is disconcerting is that there are a couple of good old fashioned Elton songs here. They are fine in and of themselves but shouldn’t have a role on a Leon Russell record. “Monkey Suit” (lyrics by Bernie Taupin, who contributes to more than half the songs) is a middling rocker that would not have been out of place on “Don’t Shoot Me, I’m Only The Piano Player” from 1972. What’s it doing here?

Also with “Never To Old (To Hold Somebody).” It’s the kind of big ballad that rejuvenated John’s career in the early 1980s. Russell sings on this tune, but he has to compete with more gospel background singers and Elton’s flowery piano.

The record closes out with a Russell composition, “In The Hands Of Angels.” This is a bit of autobiography. It’s a song of musical resurrection. Leon Russell, a couple of generations removed from “Tight Rope” and “A Song For You”, sounds plaintive, wounded and grateful. But then those goddamn gospel singers billow up again from the background.

Elton & Co. should have let all that go and allowed the grand old white haired man shine through. Next time.

‘Tuesday Morning’ Screens This Week At The New Hampshire Film Festival

October 12, 2010 § Leave a comment

Our short film, “Tuesday Morning,” screens this week during the New Hampshire Film Festival, which kicks off Thursday. If you can duck out of work early on Thursday, check it out at the Music Hall in Portsmouth, at 1:30 p.m. The picture can been seen again on Sunday at 4:30 p.m. at the Moffatt-Ladd House in Portsmouth.

We also wanted to extend our congratulations to Whitney Smith, who is nominated for best performance for her role in “Tuesday Morning.”

We were blessed with a remarkable project from start to finish, beginning with a haunting but touching screenplay by Lars Trodson, beautiful performances by Whitney and Teddi Kenick-Bailey, photography by Jonathon Millman, and the considerable talents of Stan Barker, Jason Santo, Christine Long, Mark Dearborn, Casey Mitchell, Alex Knuuttunen, Andrew Bohenko. The picture was directed by Mike Gillis.

Old School: David Fincher’s ‘The Social Network’

October 9, 2010 § Leave a comment

By Lars Trodson

The first thing we see the Internet used for in David Fincher’s “The Social Network” is an act of petty vengeance. The Internet is shown as a tool of remarkable efficiency, anonymity, and rapid-fire nastiness. These are notions that the rest of the film does not try to dispel. In fact, all we see about the Internet in “The Social Network” is a mechanism that destroys friendships, releases jealousy, initiates lawsuits and causes general unhappiness.

In this movie, trouble tends to erupt when people communicate by email, or through lawyers, or when they don’t attempt to communicate at all. In “The Social Network”, Facebook turns out to be the biggest troublemaker of them all.

Human contact, as elliptical as it sometimes can be, especially as it revolves around the lead character, Mark Zuckerberg, is always much more satisfying. It may not end well for one or more of the people involved in the conversation, but motives are at their clearest when people actually speak to each other. The fact that the dialogue is so clever has almost disguised the fact that the words said in this film are used to try to convey a feeling. There is a desperate attempt to communicate in this film. It doesn’t always work, but it’s there.

That may be why, by and large, computers, in relative terms, have a minor presence in this film. We see them ubiquitously in the early section of the film as Zuckerberg’s Face Smash program goes viral (this is the little thing where students were able to rate the appeal of various female students). But then laptops, as a tool, by and large disappear from the movie. If this is a movie about human communication, Fincher and screenwriter may be picked the wrong time in history to explore such a theme. Language as a tool for clarity and meaning is at an all-time low. We may live in an age where language is used more to obfuscate that to illuminate. So if you make a movie where language, both body and verbal, is used to try to convey something, the audience may not be with you. So far this is borne out. “The Social Network” is one of the most subtlety communicative movies you’re ever going to see and so far it hasn’t done as well as people had hoped at the box office. This is depressing.

If this is a movie about human communication, Fincher and screenwriter may be picked the wrong time in history to explore such a theme. Language as a tool for clarity and meaning is at an all-time low. We may live in an age where language is used more to obfuscate that to illuminate. So if you make a movie where language, both body and verbal, is used to try to convey something, the audience may not be with you. So far this is borne out. “The Social Network” is one of the most subtlety communicative movies you’re ever going to see and so far it hasn’t done as well as people had hoped at the box office. This is depressing.

So, what, really is “The Social Network” all about? I don’t think “the social network” referred to in the title is Facebook at all. I think the social network is people and it’s about all the messy ways we can try to communicate.

So go see the movie. And then talk about it, over coffee or a drink, face to face.